Indeed, writing on the Econsultancy blog, Karl Havard says that if you “believe there is a destination to reach, don’t put a timescale on it. Because, apologies for being the bearer of bad news, you won’t get there, you never will. Technology will continue to advance, rapidly, and behaviour will also change, you will always be playing ‘catch up’. There is no destination. Instead, you should move your focus away from the destination and to the pace of your transformation.”

Havard says the light at the end of the tunnel is not the sunshine but the tail-light of technology and all that it drives.

But others might think that asking about the timescale of digital transformation is perfectly reasonable. Shareholders and the board, for example. After all, investment in digital transformation must be accounted for.

And then there are the people expected to enact digital transformation – should their job titles and roles perpetuate?

I get tired of the analogy, but it’s true that heads of digital may one day be seen as anachronistic as the heads of electricity that companies employed in the early 20th Century. For a couple of years now, some have argued that digital is a pointless (or even inhibiting) prefix for marketers.

Five years?

In his latest digital marketing trends article, Ashley Friedlein remarks that “Digital transformation does not happen quickly. Some companies seem to expect it to happen over the course of a year. In my experience, particularly for larger organisations, closer to five years is more realistic. Even then, the task is never over.”

Five years seems to be the timespan referenced most often, partly, I would argue, because it gives enough of a nod to long-term thinking and investment without sounding like a project whose lifespan is far longer than the typical CMO’s tenure.

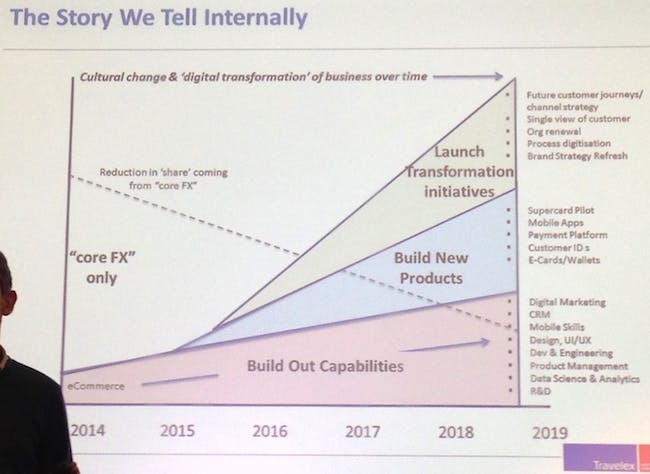

Sean Cornwell, chief digitial officer at Travelex from 2014 to 2017, when speaking at the Festival of Marketing in 2015, gave details of the five-year plan that Travelex referenced internally.

(You can read the full case study here)

McKinsey’s roadmap for digital transformation in financial services is a five-year plan, too. On its website, several authors write that “Our experience suggests that in IT alone, companies with outdated systems might need to double their current spending over a five-year period.”

The same article, when discussing investment of $950 million by Axa over two years, asserts that “investment is likely to result in lower profits for a while—but without it there is a serious risk to profits in the longer term.”

Five years might just be the figure that sounds reasonable without being too bitter a pill, but does it have much grounding in fact?

The terms ‘digital transformation’ and ‘chief digital officer’ weren’t in vogue until around 2014 and 2013 respectively (see Google Trends here and here). It therefore follows that in many cases it’s too early to tell whether five years is achievable (assuming transformation is objectively measurable).

However, there are older case studies out there. In November 2011, one-third of companies globally had an effective digital transformation program in place, according to a three-year study conducted by the MIT Center for Digital Business and Capgemini Consulting.

19 years?

One of the pioneers of digital transformation is Government Digital Services, formed in 2011 in the UK to transform government.

GDS’s Tom Loosemore gave us one of the more eloquent definitions of the word ‘digital’: “Applying the culture, practices, processes & technologies of the Internet-era to respond to people’s raised expectations.”

Defra’s CDOs Harriet Green and Myra Hunt went on to write that “digital transformation means changing working methods. It means: being more agile; putting users first; starting small and iterating from there, based on user research.”

Sharing this a lot. Good.

What we mean by Internet era ways of working:https://t.co/Hh8g9DwKap

— Tom Loosemore (@tomskitomski) October 25, 2018

But digital transformation of such a large entity as central government obviously takes longer than five years. How long?

Well, Stephen Foreshew-Cain, then exec director at GDS, in 2016 described his vision for what government will look like in 2030. That’s 19 years after GDS’s formation.

The reason for this timescale is that, as Foreshew-Cain admits, “transforming government services means transforming government itself. And that, as all of us across government have been learning over the last few years, goes much deeper than upgrading our technology and redesigning our websites.”

By 2030, Foreshew-Cain writes that “we will have fixed the basics. “Digital” won’t be a thing any more, because everything will be digital; by default. The work we’ve started in the last year to establish the digital profession in government will have matured, and we’ll have a diverse, digitally skilled workforce which reflects the diversity of the people it exists to serve.”

A pretty solid definition of a digitally transformed workplace, I’m sure you’ll agree. And if this plan is achieved, it’s reasonable to suggest that multinational companies might take just as long to transform – the best part of two decades.

A generation?

Peter Bendor-Samuel, CEO at Everest Group, asks in Forbes whether companies are making progress in digital transformation. In short, he raises the valid point of whether investment in technology happens before businesses understand that technology’s potential impact.

“[Compared to the late 1990s], We understand much more clearly how to utilize the internet, and we’ve built on top of it. Amazon and other firms leveraged the internet to create tremendous value. But most companies spent a lot of money on websites that were just sophisticated brochures. In the last 10 years, those sophisticated brochures matured and began enabling e-commerce to get much more value out of them. But that’s almost 20 years after we started the internet journey. It’s kind of shocking how long it took for those technologies to consistently take market share.

“We’re moving into the same trap again today. We now have a raft of new, disruptive technologies ranging from Artificial Information (AI) to chat bots to analytics to Robotic Process Automation (RPA), all of which collectively promise a massive breakthrough in performance. But we’re going down the same path as we did with the internet – we’re building capabilities against unproven maturity models and frameworks. If history repeats itself, which seems highly likely, much of this digital investment will be wasted.”

If what Bendor-Samuel warns of is true, and history repeats itself, it would seem to suggest that digital transformation could be the work of a generation.

Maybe, then, digital transformation is not actually a feasible goal?

Trenton Moss of Webcredible describes the period from 2017 to now as one of ‘digital transformation fatigue’.

Moss basically points out that once stakeholders learn the true costs and timescales involved (perhaps having already hired a CDO or consultancy, with no tangible results) they grow fatigued.

“Almost every traditional business (i.e. those not born in the digital age) needs to digitally transform,” Moss states, “but hardly any are talking about digital transformation anymore. And hardly any are pushing through digital transformation programs from the top-down. Instead, more-and-more digital leaders have started focusing on problem statements, ideating around how to improve operational efficiency and/or revenue and then rapidly launching PoCs (proof-of-concepts) and then MVPs (minimum viable products).

“This bottom-up approach will, over time, allow businesses to digitally transform… but without anyone mentioning the words ‘digital’ or ‘transformation’.”

Eloquently put. And backed up by the new case study of General Electric.

GE recently spun off its digital business, GE Digital, in order to streamline and make it sustainable. After big investment in the internet of things, analysts told the New York Times that such digital transformation was “overly optimistic and too broad”.

You can see a summary of GE’s digital transformation plans here, which began in 2013 when CEO Jeff Immelt said: “We know that there will be partnerships between the industrial world and the internet world. And we cannot afford to concede how the data gathered in our industry is used by other companies. We have to be part of that conversation.”

Essentially, the idea was to sell industrial engineering and the services and software that wrap around it.

Fast-forward to the end of 2018 and GE announced it would sell its majority stake in Service Max, a field management software vendor, for which it paid $915 million in 2016.

Reuters reported that “GE spent more than $4 billion building up its digital business and aimed to become a “top-ten” software company under former Chief Executive Officer Jeff Immelt.”

Is this a case study that shows Moss’s bottom-up approach is the only way to effect digital change that can make a difference in the market? Moss’s approach is certainly similar to that of GDS (who have been successful) – start small and scale up.

If we do admit, though, that digital transformation is a pipedream, that admission is not an excuse to do nothing – even if your company lacks the digital, data, martech or product management skills (plug: you can always talk to Econsultancy about that).

Final word to Karl Havard then: “there can be no excuses for standing still. Whether it’s the perception that legacy IT systems and architecture are too big and expensive to change; or there aren’t the right skill sets on board; key staff retention is poor or there’s a lack of vision and leadership; there is always a starting point. Each situation will be different, but think big, start small and scale fast….as fast as you can.”

Get in touch

See how Econsultancy can help you with your marketing effectiveness.

Comments